The Hidden Variable in Opportunity Cost

It’s wise to constantly evaluate the opportunity cost of your job.

This post was originally published on 03.06.19

It’s wise to constantly evaluate the opportunity cost of your job.

For those of us in the tech industry, a comparison is often drawn between working at a startup vs. a big company. When I started working at Facebook, I thought about this a lot (I’ll get to this later).

To compare different paths, we use values like personal fulfillment, learning potential, autonomy, compensation, community, impact on the world etc. Ideally, you work in a job which maximizes the values that are most important to you.

Your job’s opportunity cost depends on how well your job satisfies your essential values, compared to the next best alternative. Most people are pretty good at evaluating the values of their current role.

This is especially true for values that can be easily measured and compared, like compensation. It’s harder for values like fulfillment, which require a lot of introspection and can be difficult to compare concretely.

Output, or “impact”, is an important value for many people. It’s often cited as one of the primary benefits of working at a big company (your input will impact a lot of people, in some cases billions of people). Let’s refer to the scale of your impact as “surface area”.

When considering impact, there is one crucial variable which is often overlooked: efficiency. By this I mean, how much input (effort, time) is required to produce your desired output, without waste. A simple way to refer to efficiency is “pace” (this places a small bias on time as an input, which for simplicity let’s just accept for now).

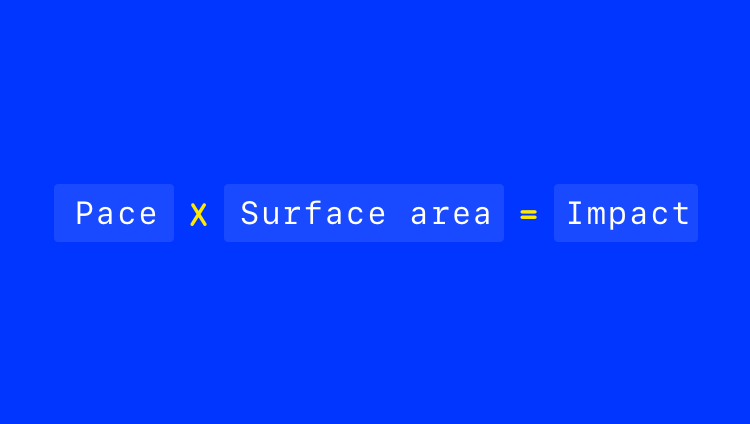

If you value impact you have to think about efficiency. The relevant equation sort of looks like this: pace x surface area = impact.

So how is impact affected by pace? Well, before we added pace as a variable, the equation was pretty straightforward: the job with the largest surface area would deliver the most impact. Pace has a dramatic impact on this equation.

In the case of a big company, the surface area is massive but the pace is very slow. It could take two years to release something that was built in one month. At a startup, the surface area is small but the pace is very fast. You could release something tomorrow that was built today.

This changes how impact is calculated, and how you should think about opportunity cost. If you aren’t considering pace, you will be misled into thinking that time isn’t relative, which is an expensive miscalculation (sort of like in Interstellar, when they get stuck on the water planet and 1 hour = 7 years).

Basically one day here DOES NOT equal one day there. You need to think about impact on a much longer time horizon to properly account for pace. Many people do not do this, which is why I’m writing about it.

Now, it’s possible that, despite an inefficient pace, your opportunity cost equation still checks out. Maybe massive surface area, even when diluted by inefficiency, still returns acceptable impact. That is definitely possible. As long as you’ve accounted for this, then you can be confident in your decision to be wherever you are.

I’ll end with a personal example. The first three years I worked at Facebook, were very efficient. I was learning insanely fast, working with incredible people, and our small team was responsible for a massive product, Facebook Live. This was an incredible experience.

Over time, my role expanded and I started working on all Video products. I worked on Live, Watch, and Social Video. I focused mostly on presence – impactful work that was deeply meaningful and fulfilling to me. I loved it.

As my role grew, so too did the size of the product teams. Team size (when not directly correlated with need) is one of the primary causes of inefficiency. What used to take days, now took months. What used to take a conversation, now took six meetings.

I’m oversimplifying, but the inefficiencies that came with these inevitable changes, changed the balance of my opportunity cost equation. I had no choice but to quit, as every additional day was actually costing me months (relative to working on the outside).

In doing so, my surface area was substantially reduced, but my pace dramatically increased. This was a trade I was willing to make, given the overall opportunity cost when considered on a long enough time horizon.

Obviously a lot more went into my decision, but “the efficiency equation” as I referred to it internally, was a large part of it.

So I say to you: consider efficiency. If you don’t, you might be making an exponentially costly mistake when deciding what to do with your life.